By Gurmukh Singh

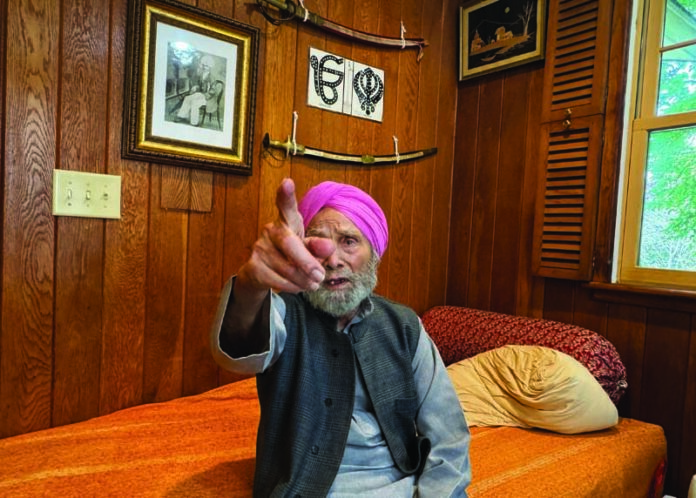

WASHINGTON DC: Touching almost 100, Dr Shamsher Singh Babra isn’t just another Indian American in Washington DC. This man is an institution.

He was the first Sikh to arrive in the US capital in 1955, and also the first Sikh to join the World Bank.

“There were hardly any Indians in Washington DC in those days – except the Indian embassy staff – when I came to this city. The few of us who were here used to celebrate various festivals at people’s homes and later at American University where I did my Ph.D. in economics,” says Dr Babra, sitting in the cozy family room of his house on the leafy Springdale Street in northwest Washington DC.

Landing in the US capital with two hundred dollars in his pocket, young Babra went on to work with the Indian Embassy and then the International Cotton Advisory Committee even as he earned his Ph.D in economics from American University.

Then the World Bank beckoned.

“My Ph.D. degree got me the job of an economist at the World Bank in 1962. I was the first Sikh to join the bank,” reminisces Dr Babra.

His face brims with pride when he quickly adds, “And now we have a Sikh – Ajay Banga – as the President of the World Bank.”

In the growing Indian community, this man has become known as Dr Shamsher Singh Babra of the World Bank.

And since this growing community had no religious place to worship and socialize, Dr Babra took upon himself the task of building a Sikh temple on some prime location in the city.

“I always nursed a dream to build a Sikh temple on the famous Embassy Row. Luckily, we found a prime piece of land. But we had to fight long and hard to get it. I donated three million dollars that I got on my retirement from the World Bank to build what is today known as the National Gurdwara on Embassy Road,” explains Dr Babra.

And at his home he hosted the who’s who of Punjab politics over the decades.

Not surprisingly, those well-versed in Punjab affairs acknowledge him as a walking encyclopedia of Sikh politics – from the tumultuous pre-Partition days to the present.

“I have personally known every Sikh leader and politician since the 1940s – Master Tara Singh, Giani Kartar Singh, Ishar Singh Majhail, Udham Singh Nagoke, Joginder Singh Mann, Gurcharan Singh Tohra, Giani Zail Singh, Parkash Singh Badal, Jagjeet Singh Chauhan, etc.,” says Dr Babra.

In fact, the late Punjab Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal and the late Punjab Minister Umrao Singh were his classmates at Sikh National College in Lahore in 1944-46.

It was at that college in Lahore that young Babra and fellow Sikh students became radicalized in response to the Rawalpindi Rape of March 1947 in which Hindus and Sikhs in the villages around Rawalpindi were massacred and women raped by Muslim mobs.

“In response, we stored gunpowder and weapons in our hostels. We were arrested and tortured. Night after night, we were moved from one location to another. The Akalis supplied us with gunpowder from Amritsar. I learnt to make bombs,” recalls Dr Babra.

On bail, young Babra was with his family in his village of Chhotian Galotian in Sialkot district when the Partition happened.

“We thought we would stay in Pakistan because we were a Sikh majority village, but then orders came for us to move to a refugee camp in Daska. From there, we moved to another refugee camp, and then crossed over into India to reach Dera Baba Nanak where we had our first hot meal in weeks,” says Dr Babra, shaking his head.

He says Pakistan founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah ordered the massacre of Hindus and Sikhs. “There is no record of this (Jinnah ordering the massacre), but we knew it then,” he claims.

He also claims that Jinnah had promised Sikhs a state if they stayed with Pakistan.

“Jinnah promised Sikh leaders to create a `Sikhstan’ if they threw their lot with Pakistan, but Sikh leaders didn’t trust him because he was very vague. If Sikhs had joined Pakistan, he would have later told them that Patiala state is already a Sikh state.”

Dr Babra says he knew American Vice-President Kamala Harris’ mother Shyamala Gopalan and her father Donald Harris.

In this interview with Canadian Bazaar, Dr Babra goes back in time and shares his life journey and thoughts with our readers.

Q: First off, in 1962 you were the first Sikh to join the World Bank. What is your reaction to a fellow Sikh – Ajay Banga – now becoming the head of the same bank?

It is a matter for great pride for Sikhs and India. Ajay Banga is a wonderful economist and analyst. He is changing the way things are done at the World Bank.

I met Ajay Banga on June 5 at a meeting of retirees whom he addressed. When I told him I was the first Sikh to join the bank, he hugged me. I am very happy for him. He comes from the Saini community and his father Harbhajan Singh Banga retired as a Lt. General from the Indian Army

Q: You knew Kamala Harris’ mother Shyamala Gopalan and her father Don Harris, right?

Yes, I knew both of them. I first met them when I went to Berkeley to meet my friend Ajit Singh who was a student there. Berkeley was the hub of the anti-Vietnam protests.

Shyamala, who came from Tamil Nadu to the US at the age of 19, was a firebrand leader, very outspoken, and very dedicated to what she believed in. She wanted the Americans to be out of Vietnam and she put her heart and soul into it. She didn’t speak mildly.

Don, who came from Jamaica, was also a student leader, but not as firebrand as Shymala. Later, they got married.

I went to meet Shyamala again when her daughters Kamala and her sister Maya were young girls of 10- or 11. Wearing pigtails and skirts, the two sisters looked smart and cheerful.

Harris, who taught economics at Stanford, needed some information from the World Bank. He called and I said come over. He came twice to meet me at the World Bank and I gave him the documents he needed for his course.

Q: So you wanted Kamala Harris to win against Trump, right?

Kamala would have made a great President. She has got all the qualities…I have watched her as the Attorney General of California and her performance has been marvelous.

We worked for her. My daughter-in-law volunteered for her. My wife also joined her. Many professional women met at our place to prepare pamphlets/cards in Kamala’s support.

Q: In Washington, you also became friends with Times of India correspondent Hans Raj Vohra whose testimony in the Lahore conspiracy case sent Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev to the gallows. What kind of a person was Vohra?

We knew about his testimony against Bhagat Singh and comrades. He was typically nobody, not very vocal about any issue. I knew him, his wife and children well. His daughter Uma married one of our friends – Satwant Grewal – and we attended the wedding.

Q: At Sikh National College in Lahore, five-time Punjab Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal was your classmate in 1944-46? What kind of a student was Badal?

Both Parkash Singh Badal and the late Punjab minister Umrao Singh were my classmates in Lahore. Out of the 560 students in the college, about 500 stayed in hostels.

We used to call all the students from the Malwa region of Punjab `Firozepurias.’ Their parents used to send them tins of pure desi ghee.

Badal was a tall, handsome young man belonging to a well-off zamindar family, but he was not good in his studies.

Badal used to take tuition from Prof Arjun Singh who taught chemistry in our college.

After two years with us, Badal left and joined Lahore’s Forman Christian College. The Akali stalwart Giani Kartar Singh, who was the president of the Akali Dal at the time of the Partition, was instrumental in bringing Badal into politics.

But Umrao Singh, who was with us in college for four years, was very popular. He played hockey for the college and took part in dramas. He was very respected by the students.

I reconnected with Badal after I joined the World Bank. When he was the Chief Minister of Punjab, he and his finance minister Balwant Singh asked me to help get funding from the World Bank for a state irrigation project. I took a team of the World Bank to Punjab and agreed to fund the project, but the Central government didn’t agree to it. In 1999, Badal released one of my books in Chandigarh.

Q: You were in Lahore when Akali leader Master Tara Singh reportedly tore the Muslim League/Pakistani flag in March 1947. Is it true that Master Tara Singh did this?

No, it is not true. Master Tara Singh never tore the Muslim League flag with his sword. Actually what happened was that the Akalis met at the Punjab Assembly in Lahore to discuss the Partition. They decided to oppose the creation of Pakistan. When they came out of the Assembly, they raised slogans and waved their swords. That’s all.

This energized us – the Sikh students of Sikh National College. From Amritsar, the Akalis (Ishar Singh Majhail and Udham Singh Nagoke) provided us gunpowder to make bombs and store in our hostels. I myself brought gunpowder from Amritsar many times and learnt to make bombs.

Then an incident happened in which two Muslim men, who were loitering in the backyard of the college hostels, were killed by the Sikh students, thinking that they were spying on them. The police, made up of mostly Muslims, raided our hostels in the middle of night. At bayonet point, we were forced to assemble on the football ground of the college. We were beaten, and taken to jail. Every night, we were shifted to a new location.

The Akalis and the Congress took up our case, moving a habeas corpus in our favour. Sikh judge Teja Singh granted us bail, but the police foisted other cases on us to stop our release.

Finally, our case went to Muslim judge Cheema who was very strict and would have jailed us for a long time. But fortunately for us, the day he was to sentence us his mother died and the case was given to another Sikh judge who released us on bail and we went to our villages. It was in May 1947, and three months later the Partition happened and we left for India.

Q: Since you knew so many Akali leaders, who were the most honest and the most corrupt among them?

Master Tara Singh and Gurcharan Singh were the two most honest leaders. Everybody knows about Badal. His wife Surinder Kaur controlled things. Badal was not even half as good as Pratap Singh Kairon. I was in India when Kairon was killed.

Giani Zail Singh was a great orator and knew how to sway people. Balwant Singh was a very well-educated leader, but his chief ministerial ambitions got him eliminated by his rivals. Tohra also met the same fate as did Captain Kanwaljit Singh.

I knew Simranjeet Singh Mann’s father Joginder Singh Mann very well. After my marriage in Rajpura, he gave us dinner at Talania village. He stayed with us in Washington as well. He also asked me to help Ganga Singh Dhillon to get out of India because of his unsavoury reputation. All these details are in my book My Land, Punjab My People, Sikhs.

Q: How did you survive the 1947 massacres and cross into India?

Our Chhotian Galotian village in Sialkot district had a Sikh majority. My father Diwan Singh, who had served in the First World War, owned agricultural land and a brick kiln. Born in 1927, I got my primary education in the village and then went to Church of Scotland Mission High School in Daska, ending up in Lahore’s Sikh National College for my higher education.

When the Partition happened, Jinnah asked Muslims to attack Sikhs and Hindus. Being a Sikh-majority place, our village became a safe sanctuary for Sikhs and Hindus from nearby villages. Then we were ordered to go to the relief camp at Daska. After three weeks, we were asked to go to another relief camp at Pasrur. Three weeks later, we crossed into India to reach Dera Baba Nanak. I will not forget till my dying day the hot roti and daal that we were served at Dera Baba Nanak. It was our first hot meal in six weeks.

Q: Then?

After three days in Dera Baba Nanak, we went to my elder brother Kartar’s in-laws in Amritsar. Everyday after our morning tea, we used to leave for the Golden Temple to eat day and night meals because we had no money.

After some time in Amritsar, we left for Delhi to live with my mother’s sister whose husband was a postmaster in Karol Bagh. They got us an apartment left by a fleeing Muslim family and we restarted our life in India.

I finished the last year of my unfinished degree course from Lahore, then did my MA in mathematics and then got involved in the local Sikh Federation politics. Later, I took up a job with the Delhi Gurdwara Committee.

Interestingly, Ishar Singh Majhail, Punjab’s rehabilitation minister, offered to give me a 85-acre lot in Karnal in 1948. But I refused as I was reluctant to get involved in farming. It was a big mistake.

Immediately after our family had settled in Delhi in 1948, I went to meet Principal Dr Tara Singh of Roorkee Engineering College. He offered me admission to an engineering degree course, but I refused it. I wondered how I would pay my college fees. That was another mistake in my life.

Q: Why did you leave India for England in 1952 when your uprooted family had just settled in the Indian capital?

I think it was a rash decision. I didn’t think how my mother would take care of the family. Because out of my Rs 200 salary, I used to give her Rs 100 to meet home expenses.

Anyhow, I sailed for England and reached London after a six-week voyage.

In London, I worked in the Indian High Commission as well as studied statistics and index numbers.

During my stay of two and a half years in London, I got acquainted with Balwant Singh Kalkat who was on his way to Washington to head the Indian Supply Mission at the Indian embassy. Since India was facing food shortage, Union Minister for Supplies Swaran Singh had appointed Kalkat to head the Indian Supply Mission to procure foodgrains from the US in Indian currency.

Later when Kalkat’s two sons came to London, I helped them too. Kalkat was so pleased that he asked me to come to Washington to join his Indian Supply Mission.

With $300 in my pocket, I immediately sailed for New York, reaching there in six days in 1955.

Q: How did you join the World Bank?

Reaching Washington, I first joined the Indian Supply Mission in the Indian embassy and also studied for my Ph.D. at American University. Two years later, I went to the International Cotton Advisory Committee where I worked for four years.

By 1962, I had finished my Ph.D. An offer to join the World Bank as an economist came and I jumped at it, becoming the first Sikh to join the bank.

During my 25 years with the World Bank, I represented it at the UN during various negotiations, handled many bank publications, worked in Ghana on economic reforms, advised Punjab on economic policy and went to Nuffield College of Oxford University as a Visiting Fellow.

After retiring as a Policy Advisor in 1987, I wrote books – Unblossomed Bud, Vichore da Dagh and Beete Punjab Da Pind – on the Partition and Punjab, and life in my village.

Q: I am told you had an interesting marriage to your Welsh wife – renamed Maldeep – in 1962 in Rajpura. How did you meet her?

We met through a common friend and had known each other for five years before tying the knot in 1962. Since I had told her that I would marry only a Sikh girl, she said she is ready to embrace Sikhism. So she went to India three weeks before me to live with my family and take amrit at Gurdwara Bangla Sahib in Delhi. Sikhs were so pleased that they took her in a procession from Gurdwara Bangla Sahib to Gurdwara Rakab Ganj. She also gave a speech which impressed the Sikh gathering.

We married at my brother’s house in Rajpura in Punjab.

Q: Any regrets?

(Sighs) Eh yatra adhuri rahi hai (it has been a half fulfilling life journey). I could have done a lot more but I got distracted and became unfocussed. To give the example of the Sikh gurdwara, I should have just given the money and delegated the responsibility of construction to others. I could have saved a lot of time and done other things.

But I have no big regrets except a few mistakes I made early in my life.

As I mentioned above, I should have accepted the post-Partition offer of the Punjab government to allot me 85 acres of land in Karnal. I should have also accepted the offer of the Roorkee Engineering College principal for admission to an engineering degree course in 1948. Also, I think I shouldn’t have left India on a whim because my mother needed me. But that is life.

Q: Finally, you are almost 100. Is it in the family genes?

Yes, I think so. My grandfather Kahan Singh lived up to the ripe age of 100. Though he suffered tragedies in life as he lost two sons to diseases, he remained a hardy person till his end. He worked two professions, including agriculture, to increase his income.

It was my grandfather who fostered the importance of education in our family because when British rule over Indians began he was very young. He analyzed that the British could rule over us only because they were very educated and skilful. He decided to give his children a good education. If not, they must learn technology.

My father Diwan Singh, who had three brothers, followed my grandfather in getting his six children a good education. The same applies to my eight grandchildren – seven boys and one girl.

READ NEXT: Parkash Singh Badal’s classmate Dr Shamsher Singh Babra recalls their Lahore college days